Your Truth Is Hurting You

You’re Not as Rational as You Think, And Neither Am I

People don’t believe what is true; they believe what is useful.

Most of our beliefs aren’t born from careful reasoning but from incentives, the invisible forces that nudge us toward what we want to be true. These incentives can come from family expectations, social pressure, indoctrination, or even our livelihood.

Early tribalism was about survival, get kicked out of the tribe, and good luck fending off predators alone. Today, our tribal instincts manifest in the teams we root for, the political parties we identify with, and the careers we depend on. Losing any of these can feel like a kind of death, so we cling to our beliefs, even when they make no sense.

As Charlie Munger put it:

“Show me the incentives, and I will show you the outcome.”

The Emotional Minefield of Beliefs

We’ve all been triggered before, somebody challenges a belief, and suddenly we’re emotional, defensive, and not exactly open to new information. That’s cognitive dissonance at work: the mental discomfort we feel when reality contradicts our deeply held views. Instead of adjusting, we attack, dismiss, or just plug our ears and scroll to the next dopamine hit.

We also love bias-reinforcing echo chambers, surrounding ourselves with people and media that validate what we already believe. It feels good. It protects our ego. And it allows us to avoid the discomfort of being wrong.

And when we do argue, we lean on logical fallacies like:

• Ad hominem (“You’re an idiot, so your argument is invalid.”)

• Appealing to authority (“A guy in a lab coat said so, case closed.”)

• Red herrings (“Oh yeah? But what about this completely unrelated thing?”)

And yes, I’ve been guilty of this too.

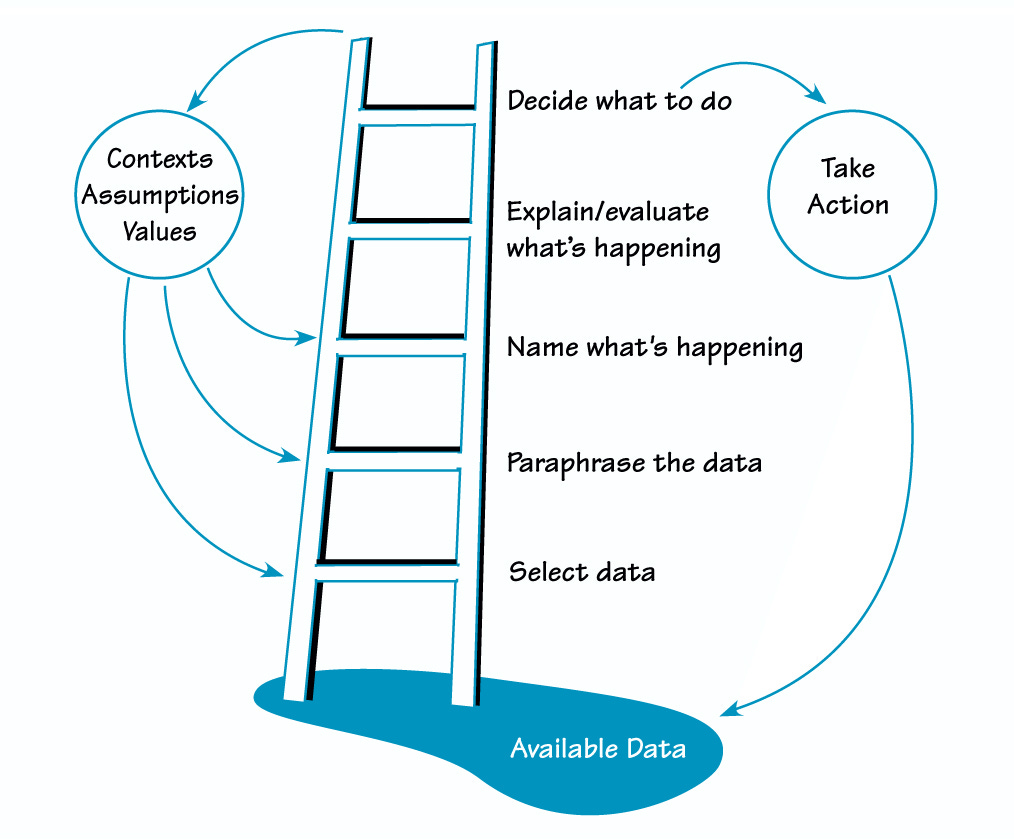

The Ladder of Inference: How We Trick Ourselves

Most of us don’t consciously decide to be wrong, it just happens naturally. The Ladder of Inference, a psychological model, explains how we process reality:

1. We observe reality, millions of bits of data per second.

2. We subconsciously filter what we pay attention to.

3. We assign meaning based on past experiences and biases.

4. We make assumptions and form conclusions.

5. We integrate those conclusions into our worldview and act accordingly.

This process happens automatically. It’s how we navigate daily life, you don’t analyze every doorknob you touch; you assume you know how it works. But this same shortcut leads us to pick and choose the facts that support our beliefs while ignoring the ones that don’t.

This is why posting a “fact-based takedown” of the other political party won’t change minds, it only reinforces cognitive bias for people who already agree with you. Social media algorithms amplify this effect, locking us deeper into our ideological tribes.

Incentives Shape Beliefs

Beyond emotions and cognitive shortcuts, our beliefs are shaped by incentives. Motivated reasoning is the brain’s way of making sure we believe whatever keeps the paychecks coming.

• Oil and gas workers may be skeptical of climate change.

• Climate scientists have every incentive to prove it’s an existential threat otherwise they may lose research grants.

• Professors who’ve spent decades on a theory won’t easily abandon it, even if new data contradicts them.

This is why you will never get someone to change their mind if their career or reputation depends on a belief being true. When faced with contradictory evidence, the sunk cost fallacy kicks in, and they double down rather than risk losing everything.

“It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it.” - Upton Sinclair

The Innovator’s Dilemma: Why Companies Ignore the Future

This same problem plays out in business. The Innovator’s Dilemma explains how once-great companies fail, not because they lack intelligence, but because they refuse to embrace disruptive technology that threatens their existing profits.

• Kodak invented the digital camera in 1975 but buried it because film sales were too profitable.

• Blockbuster could’ve bought Netflix for $50 million in 2000 but dismissed mailing DVDs because they believed in the in-store experience.

• Google was an early leader in AI but hesitated to commercialize it because AI chat models threaten their $225 billion ad-based search business.

When incentives are misaligned, even the smartest people make dumb decisions.

Emotional Resilience

Think about the most unshakable beliefs, they’re often tied to religion or philosophy. Yet, many priests, ministers, and deep thinkers don’t become emotional when their beliefs are challenged.

Why? Because they’ve deeply examined their beliefs.

This is the contrast between:

• Epistemic Rigidity – Fragile beliefs, emotionally reactive, defensive, unwilling to engage.

• Epistemic Humility – Strong beliefs, tested from all angles, able to withstand scrutiny without anger.

Religious leaders and profound thinkers anticipate challenges. They remain composed when questioned because they have mentally prepared for the argument beforehand. They also acknowledge their own doubts about their beliefs.

How to Develop Epistemic Humility

Want to be less fragile and more adaptable in your beliefs? Try this:

1. Check Your Incentives – Are you believing this because it’s true or because it benefits you?

2. Engage in Steelmanning – Can you articulate the best version of the opposing view? This takes extreme empathy and intellectual honesty.

3. Recognize Emotional Reactions – Are you mad because opposing views are wrong, or because it threatens your identity?

4. Climb Down the Ladder of Inference – Are you selecting only the facts that support your worldview?

5. Expose Yourself to Opposing Views – Not to win arguments, but to understand them.

Adapt or Be Left Behind

The strongest leaders, entrepreneurs, and thinkers aren’t the ones who cling to their beliefs at all costs. They’re the ones who challenge themselves, adapt, and update their views when necessary.

Your beliefs aren’t sacred. They should be tested, questioned, and refined. As I said in my last article Idea Scupltures, sculpt your ideas into something better by seeking out the strongest opposing views.

It’s not easy. It’s not comfortable. But discomfort and challenge is where growth happens. And right now, growth is needed.

Connect with Zach

Website • Twitter • LinkedIn • Youtube